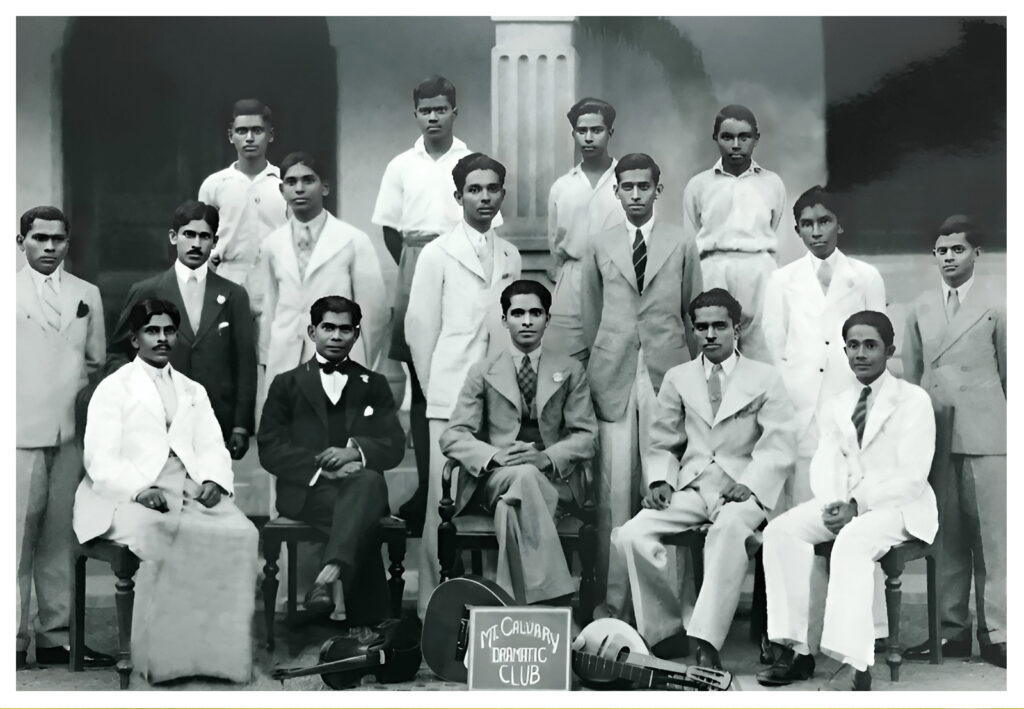

Biography

Explore the timeless melodies of Gurudevi Sunil Santha a rich collection of authentic Sinhala music that shaped a nation’s sound.

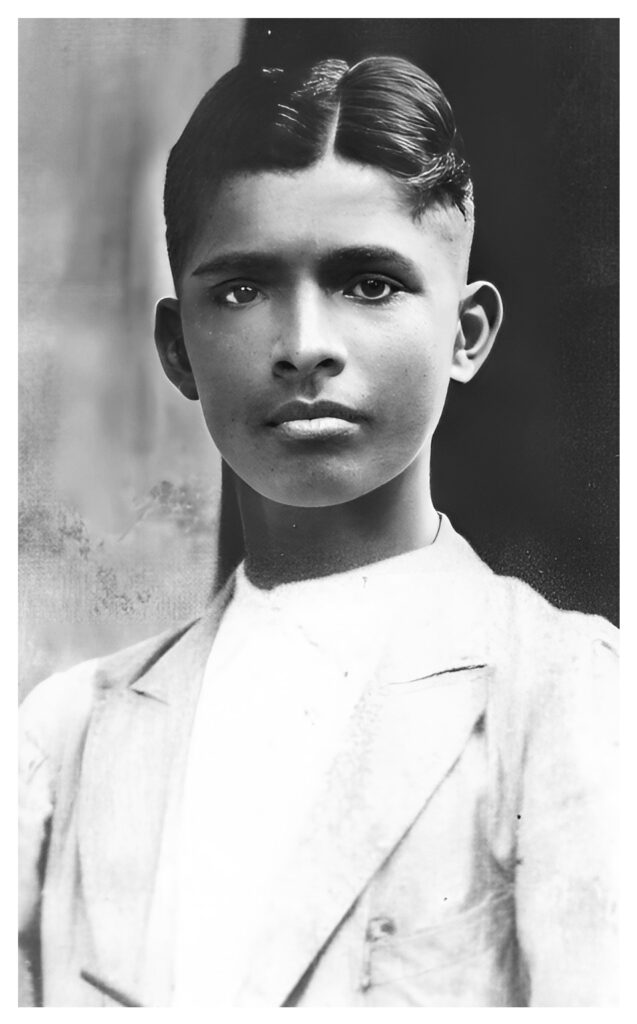

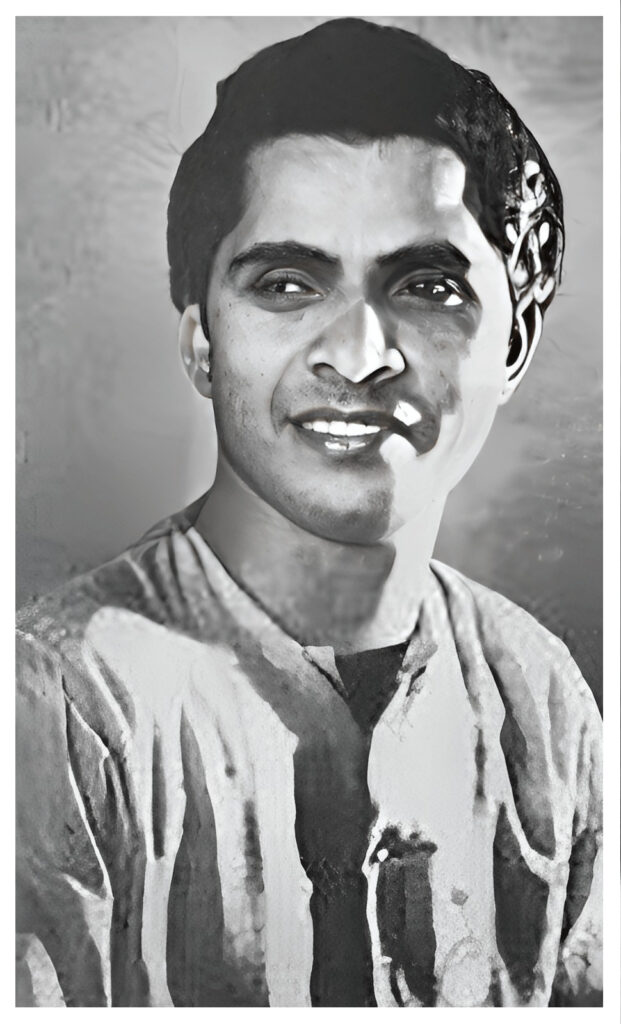

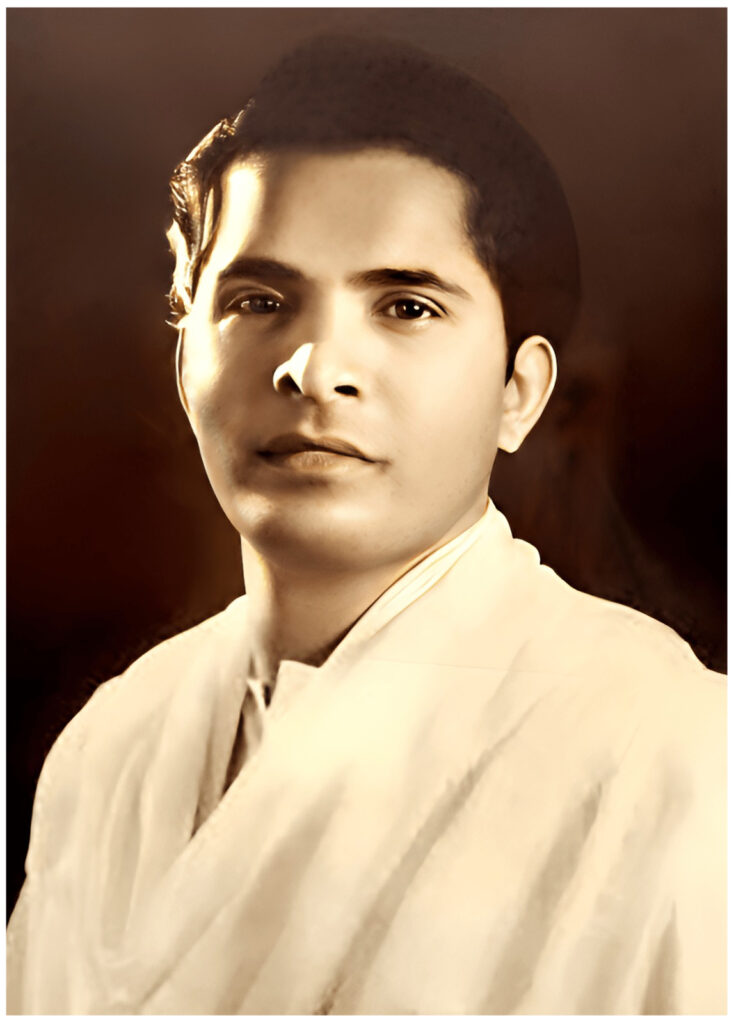

The Birth of a Legend

Early Life of Sunil Santha

On the 14th of April, 1915, in the peaceful village of Setthappaduwa, Pamunugama, a child named Baddaliyanage Joseph John was born a pious little prince and a cherished gift to the people during the festive season of Sinhala and Hindu New Year.

Baddaliyanage Don Pemiyanu and Maharage Engaltina, were his lovely parents. However, joy soon turned to sorrow. When baby Joseph was just three months old, his father Pemiyanu passed away suddenly. Following this heartbreaking loss, Engaltina returned to her native village, Dehiyagatha, with her children and settled in their ancestral home.

Tragedy struck again in 1918, when little Joseph was only three years old. A deadly contagious fever claimed the life of his mother, Engaltina, leaving him orphaned at a very young age. From then on, Joseph was lovingly raised by his grandmother in the village of Dehiyagatha.

That little boy, who overcame immense sorrow and hardship, later became Sunil Santha a monumental figure in Sri Lankan music history, who reshaped the sound of a nation with his deep-rooted love for indigenous melodies.

The Roots of a Timeless Voice

Education and Musical Mastery

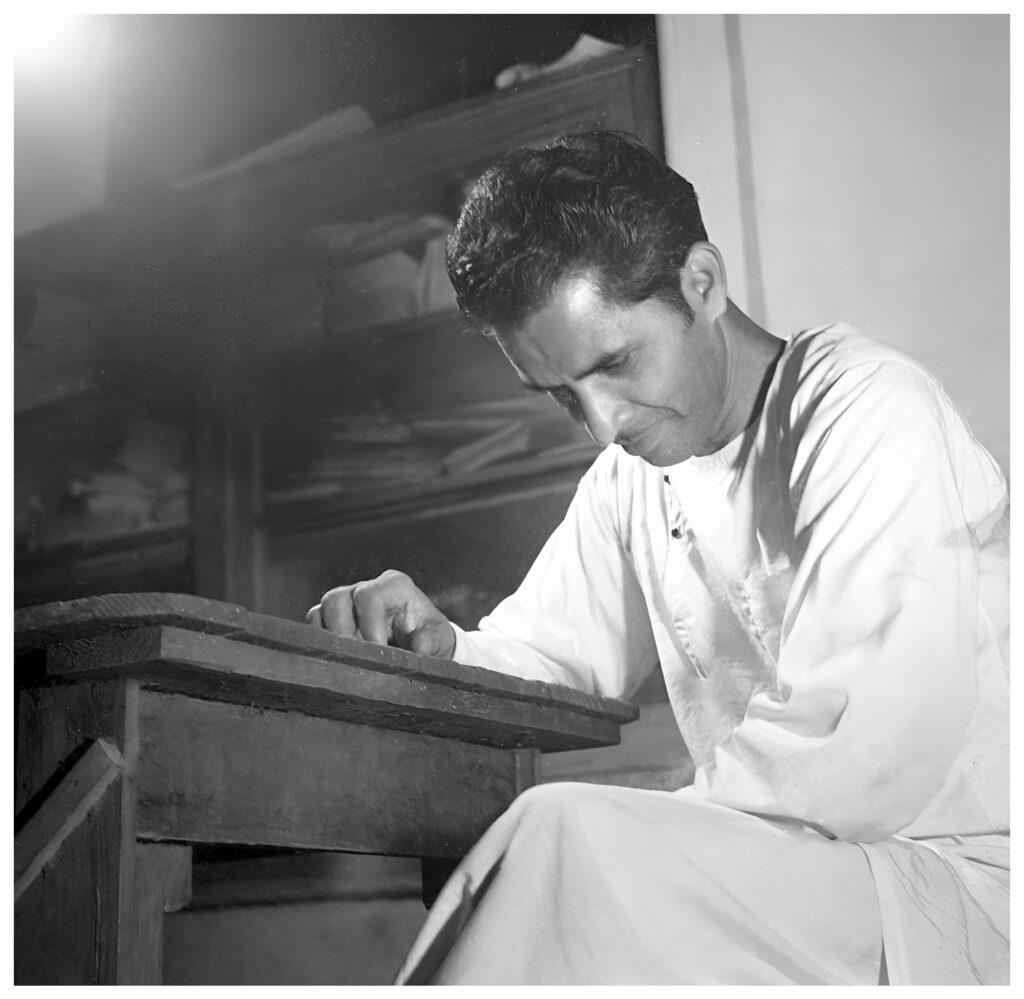

Sunil Santha’s journey into music was not a mere coincidence of talent it was the outcome of an extraordinary academic foundation, bold choices, and an unwavering pursuit of mastery.

Born as Baddaliyanage Don Joseph John, Sunil Santha’s academic brilliance shone early. In 1931, he topped the island in the School Leaving Certificate Examination an equivalent of today’s A/Ls becoming the best performing student in Ceylon. Initially pursuing a career in teaching, he trained as a Sinhala teacher and was known for his love for invention, language, and exploration of knowledge.

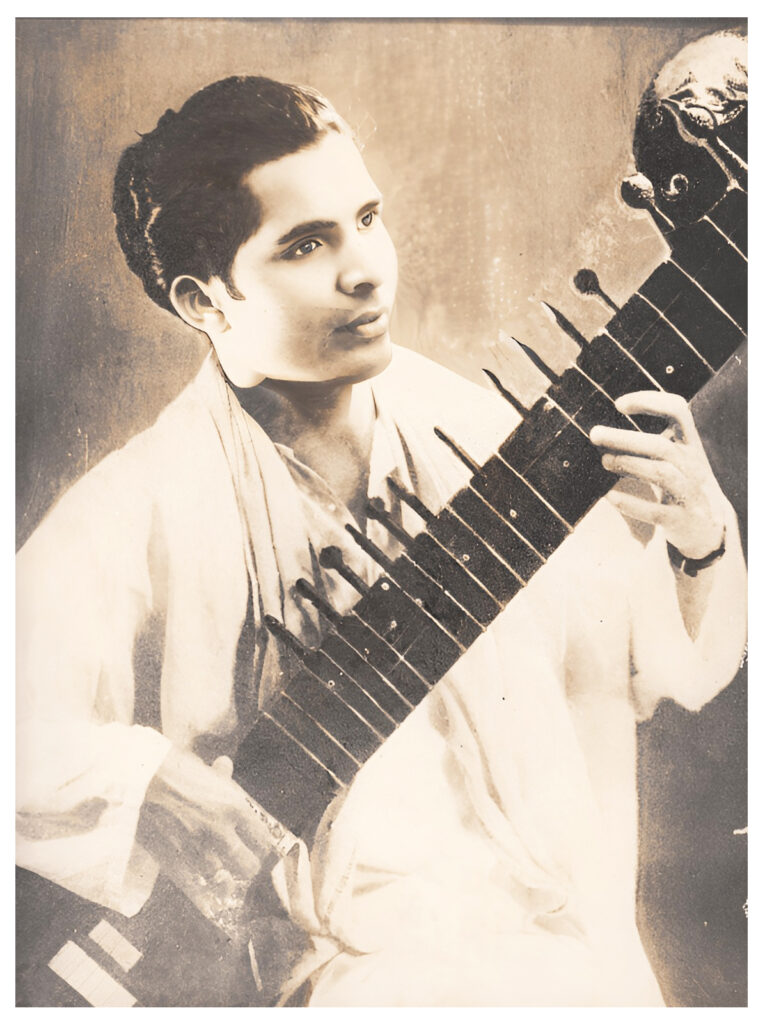

But it was music that truly called him. In 1939, he enrolled at Santiniketan, the cultural university founded by Rabindranath Tagore. After a year immersed in the arts and philosophies of the East, he transferred to Bhatkhande Music University in Lucknow, India Asia’s most prestigious institution for Hindustani music.

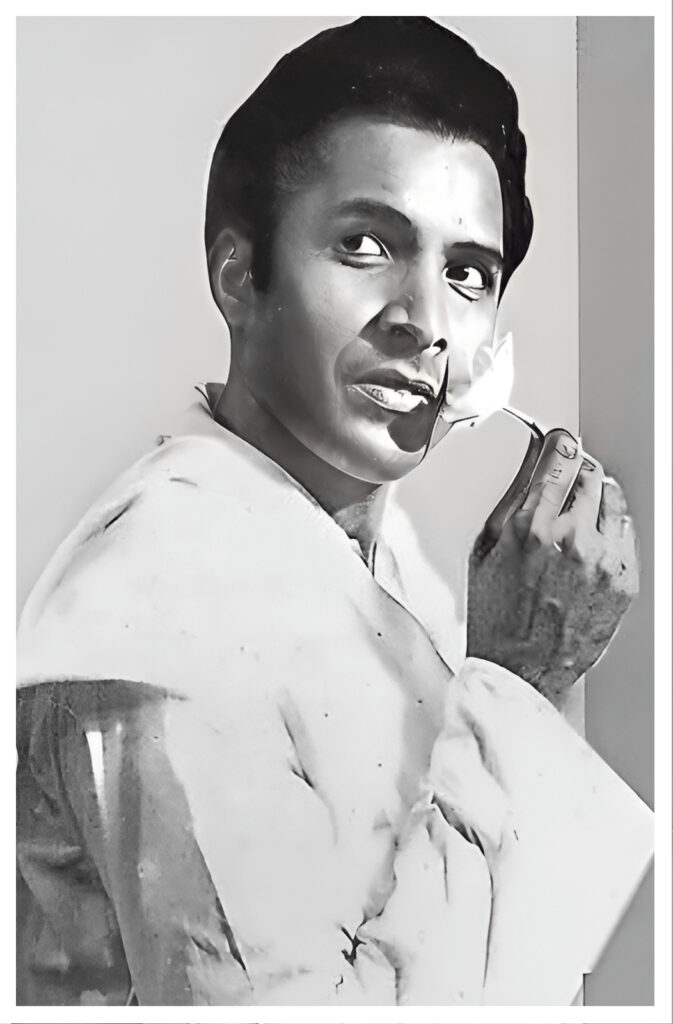

At Bhatkhande, Sunil Santha broke boundaries and records. He became the first non Indian to graduate as the best student, receiving the rare distinction of Visharad in both Vocals and Instrumentals (Sitar) a dual honor almost never awarded to a single student. His powerful and nuanced voice earned him the nickname “The Golden Voice of Ceylon”, and he led his batch with the highest marks in instrumental music in 1944. Professors and peers alike acknowledged his unmatched vocal training and creative instincts.

More than just a scholar of Indian classical music, Sunil Santha possessed an expansive knowledge of Western classical, Hawaiian, and Bengali musical traditions. But what truly set him apart was his vision to blend this global knowledge with the heartbeat of his homeland. He immersed himself in Sri Lanka’s indigenous rhythms, from Dalanda Perahera tunes to Sigiri Gee, and forged a new genre of modern Sinhala music that was as scholarly as it was soulful.

He was also a rare triple threat in the music world: a composer, lyricist, and singer capable of creating masterpieces from start to finish. He sang fluently in Sinhala, English, Hindi, and Bengali, even recording the first English playback song in a Sinhala movie in 1967, which critics likened to the stylings of Jim Reeves.

His contribution to the arts didn’t stop at performance. Sunil authored and published music books, mentored the next generation of musicians (including greats like W.D. Amaradeva and Victor Rathnayake), and even taught music through Radio Ceylon’s national broadcasts reaching homes across the island with structured, inspiring lessons.

His educational ethos was matched by integrity. He refused to commercialize his legacy or re-sing his youthful hits when he felt he couldn’t match their original vocal quality. For Sunil Santha, quality, originality, and authenticity weren’t just ideals they were non negotiables.

In an age when most musicians were bound by traditions or market trends, Sunil Santha emerged as a fearless innovator one who used education as his launchpad, not his limit. His intellectual foundation, rare artistic training, and fearless creativity laid the groundwork for a uniquely Sri Lankan musical identity that still echoes today

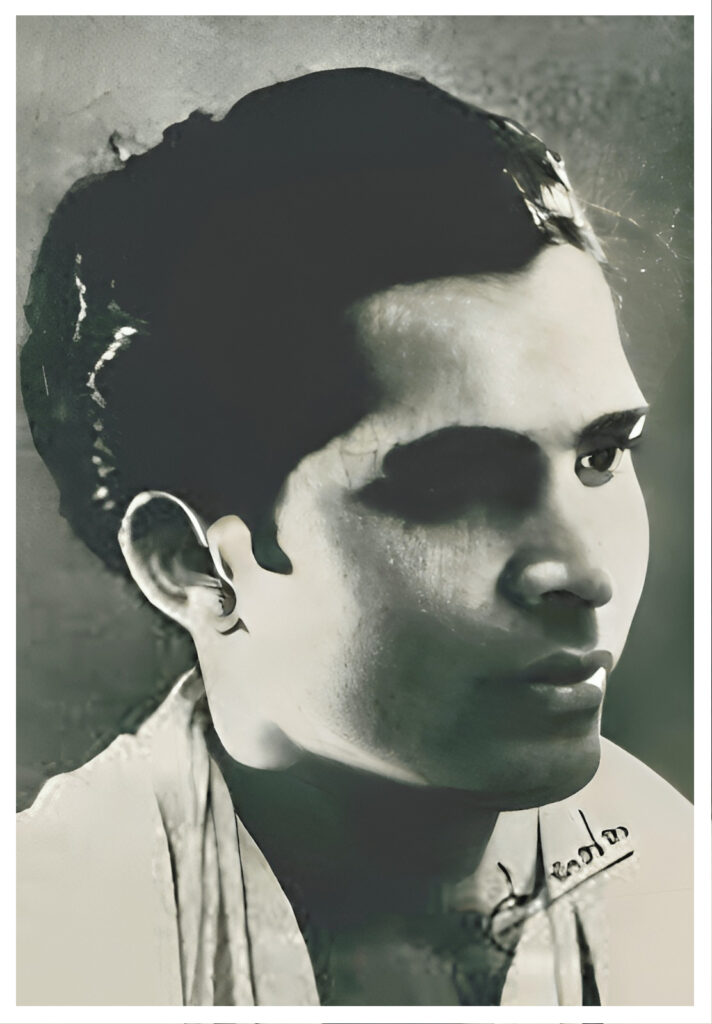

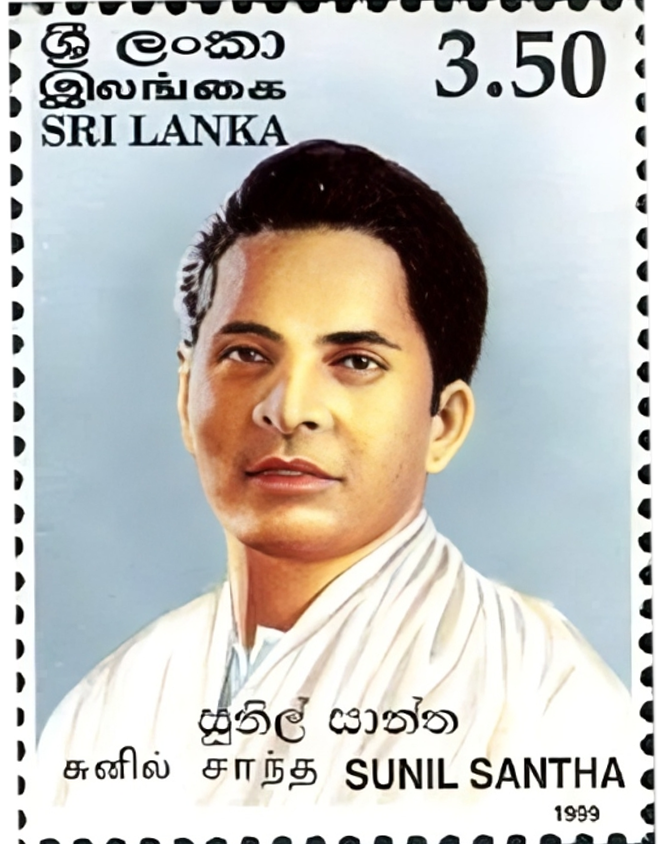

The Birth of a National Voice

Sunil Santha’s Musical Breakthrough and Rise to Fame

When Sunil Santha returned to Sri Lanka in 1944 as the top graduate of the prestigious Bhatkhande Music University in India, he came back not only as a musician but as a visionary. Armed with the dual title of Visharad in both vocals and instrumentals, and celebrated as the “Golden Voice of Ceylon,” he stood on the edge of history, ready to redefine the very soul of Sinhala music.

A Genius Without a Platform

Despite his unmatched academic achievements and international acclaim, Sunil was offered a modest post as a Physical Education teacher at a public school. Sri Lanka, still tethered to colonial mindsets, failed to recognize the treasure that had returned home. Yet, Sunil did not protest. He quietly began his mission to create a musical tradition that was authentically Sri Lankan, rooted in native identity and soul.

The Disc That Changed Everything

In 1946, the winds began to shift. That year, Radio Ceylon Sri Lanka’s only broadcasting station at the time imported a brand-new disc cutting machine to modernize its recording capabilities. Who would they invite to inaugurate it? None other than Sunil Santha. His debut recordings, “Olu Pipila” and “Handapane,” became instant classics. These songs weren’t just hits they were milestones, marking the birth of modern Sinhala music. For the first time, the island heard a singer who didn’t imitate Hindustani tunes or Western pop but brought to life the melodies of its own land. The lyrics were in pure, simple Sinhala, the music resonated with native rhythms, and the vocals carried a trained grace never heard before. With that, Sunil Santha became a national voice.

A Star is Born

Almost overnight, Sunil became the first musical superstar of Sri Lanka. His songs cut across class divides sung in elite households, village temples, schools, and bustling market squares. His image tall, charismatic, and confident added to his allure, and he was soon invited to perform at packed musical shows across the country. Pioneering choreographer Chitrasena frequently invited Sunil to sing during dance intervals to draw large audiences. Even the daughter of the British Governor-General became a fan and recorded cover versions of his songs. His music notebooks, containing notations and lyrics, sold widely, earning him enough to purchase a motorcar an incredible feat for a Sri Lankan artist in the 1940s.

Redefining the Sound of a Nation

At a time when most Sri Lankans consumed either Western music, Hindustani ragas, or Indian film songs, Sunil created a third path: Sinhala music for Sri Lankans, by a Sri Lankan. He skillfully blended Hindustani classical, Bengali lyricism, Western harmony, and most importantly, the indigenous Sinhala folk tradition. His songs told stories of patriotism, love, nature, and cultural pride in a language and tone that resonated deeply with the hearts of his people. This bold innovation opened what could only be described as a musical blue ocean. For the first time, all classes of listeners urban elites, middle-class youth, rural villagers found common ground in music. He unified a diverse audience with melodies that were both deeply rooted and strikingly modern.

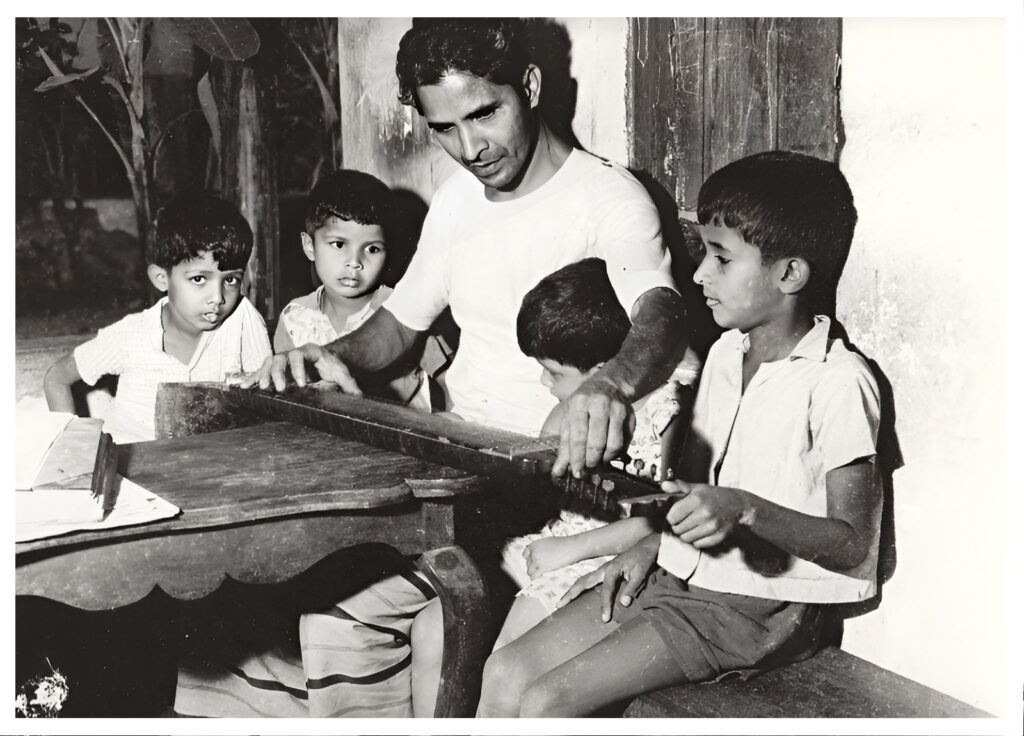

A Mentor in the Making

Beyond performance, Sunil saw his role as a teacher and mentor. He launched music classes, published songbooks, and even conducted music education sessions over the radio. Among his earliest students were young talents like W.D. Amaradeva, Patrick Denipitiya, and Ivor Dennis who would go on to shape the next generation of Sri Lankan music. His classes weren’t just about technique they were about musical philosophy. He taught his students to compose and sing with heart, discipline, and cultural consciousness. He nurtured in them what he called “Sri Lankan musical intuition” a deep connection to the island’s soundscape.

Creating a Cultural

Identity In less than six years from 1946 to 1952 Sunil Santha accomplished what few could in a lifetime. He shifted the trajectory of Sri Lankan music from imitation to innovation. He wasn’t just entertaining a nation he was shaping its cultural identity. His rise to fame wasn’t driven by commercial ambition but by a mission to help Sri Lankans hear themselves, love themselves, and believe in themselves. As his star rose, so did the tensions. The gatekeepers of tradition, the adherents of Indian classical orthodoxy, and the emerging academic cliques in university circles saw his ideas as a challenge to their authority. Jealousy and ideological conflict would soon pave the way to an orchestrated downfall. But before that, Sunil had lit a fire that could not be put out. His voice had become more than melody it had become a movement.

The Fall

The Ratanjankar Test and the Conspiracy That Silenced a Legend

At the peak of his musical career, when his voice echoed through the homes and hearts of Sri Lankans, Sunil Santha faced a fate few visionaries are prepared for: being punished for being ahead of his time. What unfolded in 1952 was not just a personal tragedy it was a cultural crisis that derailed the course of Sri Lanka’s authentic music evolution.

A Threat to the Establishment

Sunil Santha’s meteoric rise as the founder of modern Sinhala music unsettled many in the academic and musical elite. His rejection of Hindi-influenced musical templates, his insistence on originality, and his fearless critiques of plagiarism and mediocrity made him a marked man. The existing music establishment, tightly linked with universities and power brokers, saw Sunil not as a peer but as a disruptive force challenging their hegemony.

The Trap: Ratanjankar Test of 1952

In a move framed as an “administrative standardization,” Radio Ceylon Sri Lanka’s only broadcasting entity at the time introduced a compulsory evaluation for all its performing artists. The test would be conducted by none other than Prof. S.N. Ratanjankar, principal of Bhatkhande University, the very institution where Sunil had graduated as top of his class.

On the surface, it appeared routine. But beneath, it was a calculated maneuver to undermine Sunil Santha’s credibility.

Sunil’s Objection and Stand

Sunil Santha, once Ratanjankar’s prized student, refused to take part in the test not out of arrogance, but on principle. He publicly voiced his opposition:

- Why should a qualified Visharad and batch-top graduate be re-evaluated alongside novices, many of whom he had personally trained?

- Why was an expert in Indian music traditions chosen to assess a uniquely Sri Lankan musical style?

- Was this really about quality or a backdoor plot to reassert Hindustani dominance over Sri Lankan music?

Sunil rightly saw that this test would push musicians toward Indian styles for better scores, thus eroding the foundations of an emerging Sinhala musical identity.

The Cost of Integrity

When Radio Ceylon refused to listen, Sunil walked away choosing dignity over compliance, even if it meant financial ruin and professional exile. His decision cost him dearly: he lost his platform, his income, and access to the only national broadcasting outlet. After his departure, his music was unofficially banned. His recorded discs at Radio Ceylon were scratched and vandalized. His name was systematically erased from playlists and public events. The media, once enamored by his brilliance, grew silent. Yet, Sunil Santha never wavered.

Years in the Shadows – Life After Silence

After his principled exit from Radio Ceylon in 1952, Sunil Santha entered what can only be described as years in the shadows a prolonged period of forced silence, creative exile, and quiet resilience. It was not artistic failure or fading relevance that muted his voice but the cold politics of cultural gatekeeping. Radio Ceylon made a silent decision to erase the sound of the man who had taught the nation to sing in its own language.

Stripped of his livelihood, Sunil turned to other trades to support his family: electrician, photographer, fish vendor, mechanic, mason jobs far removed from the concert halls he once filled. His beloved instruments lay unused, his songs unheard, his disciples heartbroken.

But even in silence, he remained the voice of integrity never begging for favors, never compromising for re-entry. He waited, hoping one day Sri Lanka would realize the injustice it had done.

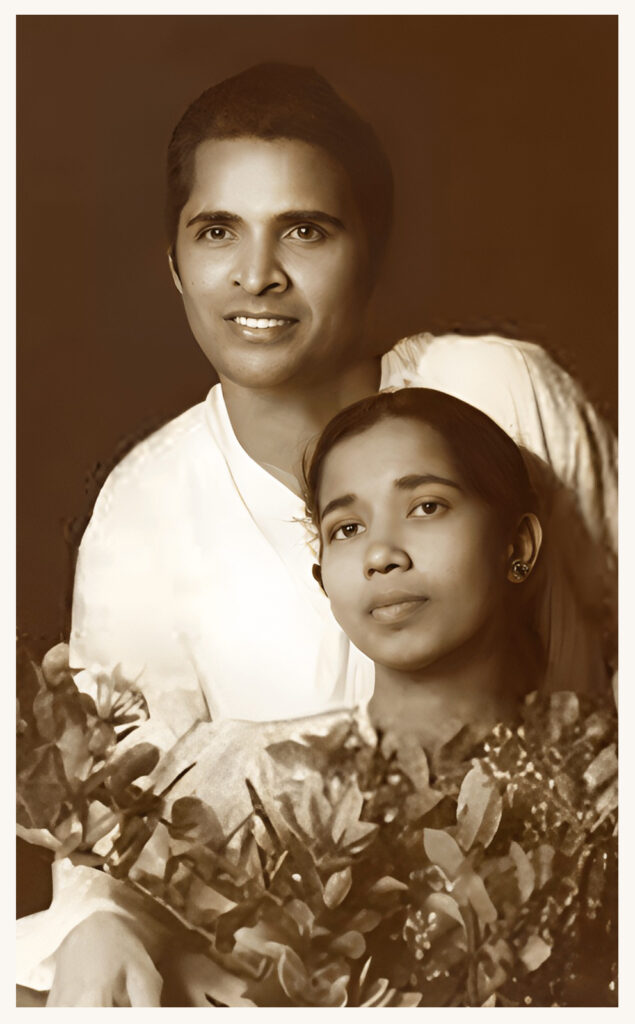

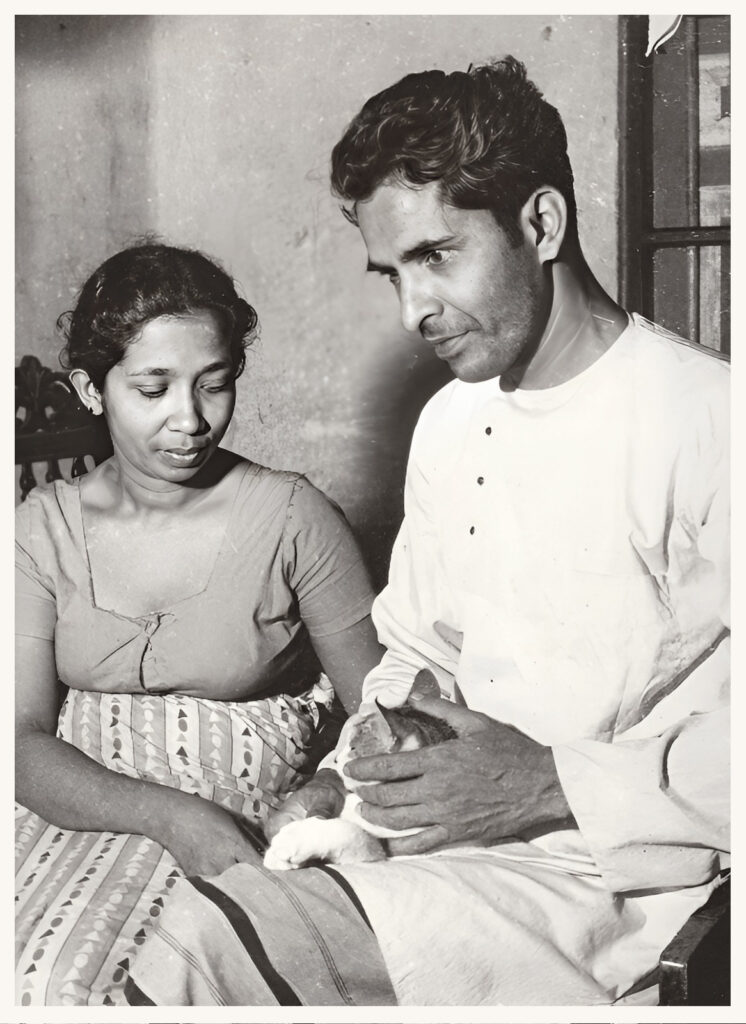

The Heart Behind the Genius – His Family

In the midst of this struggle, Sunil Santha’s greatest source of strength was his family. He was married to school teacher Bernadet Leelawathi Jayasekara, a kind-hearted, resilient woman who stood by him through every hardship. Together, they had four children three sons and one daughter.(Sunil, Lanka, Jagath & Kala)

Sunil was a loving father and fiercely protective husband. Even as financial stress mounted, he made it a priority to ensure his children received a strong education. He taught them values of integrity, creativity, and resilience not just through words, but by example.

- All three sons became engineers, a remarkable achievement given the family’s challenges.

- His daughter became a veterinary surgeon, reflecting the deep emphasis on discipline and learning within the Santha household.

A Legacy Interrupted, Not Broken

In 1955, director Lester James Peries invited Sunil to compose the score for Rekhava the first Sinhala film with a fully Sri Lankan soundtrack. Though hesitant, Sunil accepted. His hauntingly original compositions brought international acclaim, with Rekhava becoming one of the first South Asian films screened at the Cannes Film Festival.

The Return

A Glimmer of Recognition

(1967–1969)

In 1967, a new era dawned at Radio Ceylon, now renamed Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC). Its newly appointed Chairman, Neville Jayaweera, sought to revitalize the institution by reconnecting with its true pioneers. Upon discovering that the man behind the very first Sinhala disc recordings Sunil Santha had been sidelined for 15 years, Jayaweera was both shocked and determined to correct a national wrong.

Sunil was invited to sing “Olu Pipila” at a live commemorative broadcast. The response

was overwhelming: audiences wept, applauded, and flooded the station with calls

and letters. It was as if a long-lost voice had returned from exile. Moved by the public’s

affection, Jayaweera offered Sunil a position at SLBC and asked him to oversee a renewed

artist classification panel the very process that had once destroyed him.

Sunil agreed, but only on one condition: fairness. He restructured the audition system

into a three-member panel that included himself, a senior musician (Rupasinghe

Master), and a younger generation representative (W.D. Amaradeva). It was a gesture

of transparency, wisdom, and forgiveness showing Sunil’s focus had always been on

uplifting music, not settling scores.

Rekindling the Flame – A Brief Return and Creative Renaissance

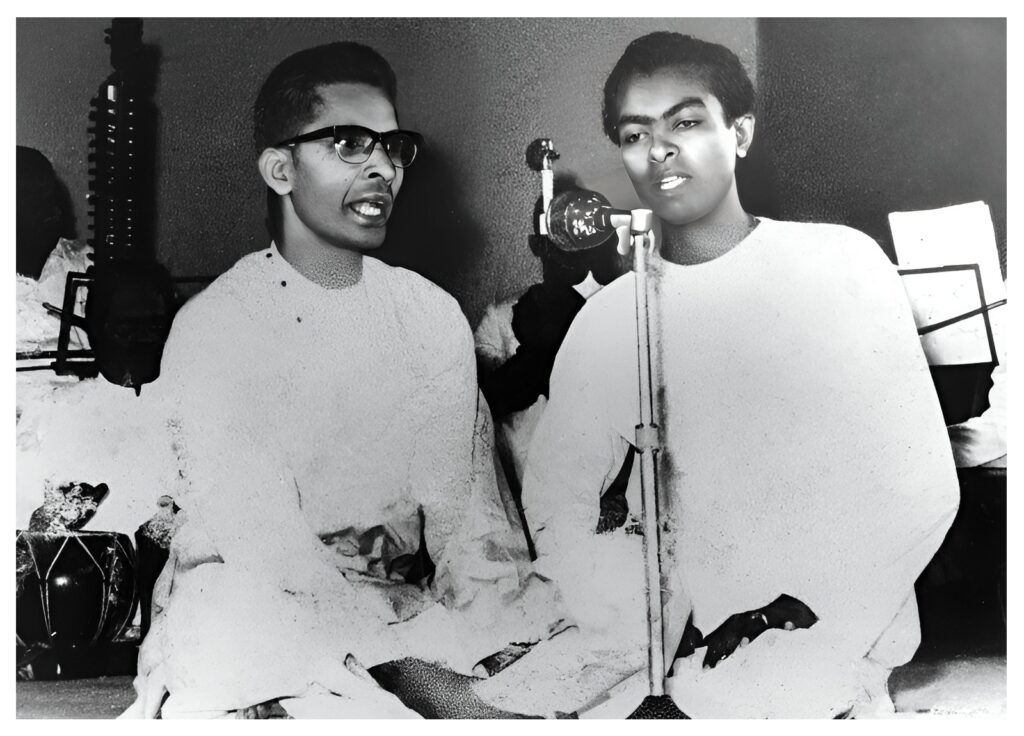

In 1967, Sunil Santha was invited back to the newly formed Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC) under the chairmanship of Neville Jayaweera, who sought to right past wrongs. His return marked not just a reinstatement, but a creative renaissance. Though brief, this period saw some of the most experimental, visionary, and deeply Sri Lankan contributions Sunil ever made.

One of his landmark contributions was composing melodies to Sigiri graffiti ancient

poems etched on the mirror wall of the Sigiriya rock fortress, dating back over 1,500 years.

While most musicians dismissed these inscriptions as mere literary curiosities, Sunil

sensed the musicality buried within. He composed melodies for four such verses,

capturing the voice of a civilization lost to time and recording them using instruments that

resembled those used in ancient eras. This remarkable feat bridged the past and present,

showing Sunil’s unparalleled musical intuition and historical sensitivity.

During this period, he also composed the world’s first complete one-note song a bold

experiment in vocal modulation and rhythmic variation. Though minimalist in tone, the

song was rich in emotional layering and artistic depth, proving that complexity could

emerge from simplicity when guided by genius.

Sunil also worked with his protégés to craft a series of experimental songs that explored

themes like environmental harmony, universal love, and positive thinking. These

compositions broke free from the sorrow-laden traditions that had dominated Sinhala

music since his absence. His melodies invited joy, upliftment, and a reawakening of

cultural pride.

His return also brought forth the English playback song “My Dreams Are Roses”, featured in a Sinhala film. Sung with a tone reminiscent of Jim Reeves, it was praised internationally and remains a testament to his vocal adaptability and international appeal.

Moreover, Sunil revived and reshaped the use of Sinhala folk music in national programming. He curated broadcasts that emphasized traditional instruments, indigenous rhythms, and native storytelling styles. In doing so, he reasserted that Sri Lankan music did not need to borrow its identity it already had one, waiting to be honored.

Despite the brevity of this return (1967–1969), the impact was monumental. It was not just a personal revival; it was a reaffirmation of a musical philosophy rooted in authenticity, pride, and national consciousness.

Sunil’s fire, though long suppressed, burned brightly once again proving that a true artist’s flame can flicker in silence, but never be extinguished.

A Silent Giant in Cinema

Though no longer widely active, Sunil Santha was still respected by visionary filmmakers like Dr. Lester James Peries, who recognized his unmatched ability to create emotionally resonant, authentically Sri Lankan melodies. After Rekhava in 1956, Sunil was invited again to compose for “Sandeshaya” (1960), producing timeless songs like “Rejina Mamai,” “Rena Gira,” and “Sudu Sanda Eliye” melodies that became etched in the nation’s collective memory.

Later, in 1976, he composed a piece for the film “Kolomba Sanniya,” once again proving that even with minimal exposure, his work could outshine prevailing trends.

The Final Years: Dignity in the Face of Neglect

Though revered by the public and some segments of the artistic community, Sunil remained unofficially blacklisted from frequent airplay. SLBC, dominated by the same academic-cultural clique that ousted him in 1952, continued to keep his music in the shadows. In the late 1970s, a commercial sponsor offered Sunil a lucrative contract to sing his old hits again for a new variety show. But he refused. “I can still compose and sing new songs,” he said, “but I won’t revisit my old recordings if I can’t do them justice. The people deserve better.” Even in hardship, he remained unshakably ethical.

The Final Curtain – Sunil Santha’s Last Days and Death

By the dawn of the 1980s, Sunil Santha was no longer at the center of Sri Lanka’s musical stage—but he remained a towering figure in spirit. Though he had long been pushed to the periphery by institutional neglect, his inner fire had not gone out. He continued to live a humble life, full of personal discipline, dignity, and silent strength.

Despite years of disappointment and hardship, Sunil never expressed bitterness. Instead, he remained loyal to the ideals he had always lived by: authenticity, cultural pride, and doing what is right even if no one else noticed.

Tragedy struck in early 1981, when Sunil’s youngest son, Jagath, drowned under tragic and mysterious circumstances. Jagath, an engineer, was intelligent, full of promise, and dearly loved by the family. His untimely death delivered a devastating emotional blow to Sunil. For a man who had endured public betrayal, creative exile, and financial hardship this personal loss was the one wound he could not bear.

Though outwardly composed, those close to him could sense that something within had broken. Just six weeks after Jagath’s death, on April 11, 1981, Sunil Santha passed away from a heart attack, at the age of 66.

He died not in celebration or honor, but in quiet obscurity without a state funeral, without national tribute, and without the radio waves that once carried his songs across the island. The institutions that had once benefited from his genius remained largely silent.

But in homes across the country in the hearts of those who grew up with “Olu Pipila”, “Handapane”, “Ridee walawe”, and “Lanka Lanka” a deeper grief stirred. The people knew what the system had tried to forget: that a true master had passed away.

Sunil Santha’s body was laid to rest. But his spirit rooted in the sound of a nation, the rhythm of its language, and the melody of its heritage never left.

The Legacy

Disciples, Influence, and Revival

Though his voice was silenced far too early, Sunil Santha’s influence never truly disappeared. Like a deeply rooted tree whose branches reach far beyond the eye, his legacy lives on through his disciples, his principles, and the quiet resurgence of the music he pioneered.

A Mentor Beyond Measure

Sunil Santha was more than a musician he was a master teacher. His methods were not just about scales and technique, but about instilling identity. He believed that to create authentic music, one had to first understand one’s land, people, and language.

Among his most well-known students were:

- Pandith W.D. Amaradeva, perhaps the most famous figure in Sinhala classical music

- Ivor Dennis, whose voice so closely resembled Sunil’s that he continued to sing Sunil’s songs for decades, keeping his melodies alive.

- Patrick Denipitiya, an immensely talented composer and performer who brought a new dimension to Sinhala music through guitar and orchestral work.

- Victor Rathnayake, later hailed as one of Sri Lanka’s finest vocalists, emerged during the second phase of Sunil’s work at SLBC.

But beyond these giants, Sunil taught and inspired hundreds of young students, many of whom became music educators, broadcasters, and quiet torchbearers of his style.

A Style That Sparked a Movement

Sunil’s music was unmistakably Sri Lankan rooted in folk traditions, village melodies, temple chants, and the rhythms of nature. His use of pure Sinhala language, simple lyrical imagery, and melodic clarity set his music apart from the dominant Hindi influenced or Western-adopted tunes of the era.

He envisioned music as something more than entertainment it was a tool for national awakening, a cultural declaration of independence.

Many later artists who didn’t study under him directly still drew influence from his vision. Even musicians like Clarence Wijewardena, C.T. Fernando, who explored popular styles, operated in a musical environment made possible by Sunil’s early work of creating space for Sinhala-language music to thrive.

The Silence That Followed and the Echo That Returned

For decades after his death in 1981, Sunil Santha’s name was curiously absent from textbooks, media, and public tributes. His contributions were often downplayed or absorbed into the achievements of others.

But slowly, his story began to resurface.

- Most importantly, in 2025, the same institution that once removed him Radio Ceylon (now SLBC) formally and publicly declared Gurudevi Sunil Santha as the foremost national hero of Sinhala music in Sri Lanka. This long-overdue recognition marked a turning point in how the nation remembered its musical roots.

- Dr. Ruwan Ekanayake, who authored a monumental three-part volume on Sunil Santha’s life, music, and cultural vision. This comprehensive study not only chronicled his journey but also analyzed his philosophies, compositions, and unique approach to national identity through music.

- Scholars like Prof. Tony Donaldson (Australia) and Dr. Nandadasa Kodagoda began writing about his unique vocal technique and musical theory.

- Former students and admirers organized tribute concerts and re-releases of his original recordings, reminding Sri Lanka of the voice it had forgotten.

- In recent years, new generations have begun to discover his work via digital archives, YouTube playlists, and cultural programs. His compositions, once pushed into silence, are now studied again with renewed respect and wonder.

The Work Ahead

Today, there is a growing call to formally recognize Sunil Santha as the father of modern Sinhala music. Proposals have been made to:

- Establish a Sunil Santha Music Institute to train artists in his philosophy and method.

- Integrate his contributions into school music curricula and university syllabi.

- Restore and archive his full body of work recordings, writings, unpublished compositions under one national digital platform.

- Document his life and legacy through films, documentaries, and exhibitions.

At the grassroots level, the Sunil Santha Samajaya is actively carrying this torch forward by conducting several landmark projects, including:

- “Waren Heen Sare” – a tribute concert blending traditional and modern styles to introduce Sunil Santha’s music to younger audiences.

- The Sunil Santha Memorial Discussion Series, which brings together musicians, academics, and cultural figures to analyze and reflect on his contributions.

- Various initiatives such as school outreach programs, digital restoration projects, and archival efforts aimed at preserving and promoting his vision.

The mission is clear: to ensure that Sunil Santha’s name, music, and philosophy remain not only a part of Sri Lanka’s past but an enduring beacon for its cultural future.

His Legacy Lives On

Sunil Santha’s legacy is not just in the music he left behind but in the courage to be original, the refusal to conform, and the belief that a small island could sing its own song to the world.

His work reminds us that true cultural identity is not borrowed it is built, through vision, sacrifice, and soul.